In light of that, I’ve come up with a list of four terms that have been at the heart of the disputes, implicitly or explicitly, and try to explain what they may stand for on the two sides of the Atlantic, adding to what was already written here. In doing so, I have no intention of unifying opinions, because I get the sense that there are deeply rooted differences that go back at least three centuries and therefore can’t be cleared away with one stroke. But hopefully it can clarify the whys, even if it doesn’t change their outcome, so we at least know where we’re coming from and agree to disagree.

Keep in mind, though: as with the previous posts on the divide between US American and western European polytheists, this is written primarily from the perspective of someone of was born and raised in Portugal. A lot of what I say may be true in other parts of the continent, but Europe is not monolithic and there are some differences between north and south and especially east and west. The same is true about the United States, as there are certainly many US polytheists who do not see themselves in the opinions of several of their fellow countrymen/women. Ultimately, this is about specific and contrasting trends, not unanimous views on either side of the Atlantic. Also, this is a very long post.

1. Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was a complex and multifaceted period that extended from the mid 17th century to the late 18th and had a deep impact on Europe’s political, religious and scientific culture. It basically marked the beginning of the end of the old system, which broadly consisted of autocratic monarchies with little or no tolerance towards political and religious dissent, ruling over societies where the Church retained an overwhelming influence over knowledge and learning and the social fabric was still by and large feudal. The major exceptions were England and the Netherlands, where power was less centralized and there was a degree of religious tolerance, especially in the latter of those two countries.

As an alternative to the old order, thinkers like John Locke (1632-1704), Montesquieu (1689-1755), Voltaire (1694-1778) and Rousseau (1712-1778) defended the notions of social contract, of government by the consent of those governed, of natural and unalienable rights such as life and liberty, of separated powers to create checks and balances, of knowledge through experimentation and critical analysis, of education as a way of raising well-informed and able citizens, of greater religious tolerance and also separation of Church and State. Of course, none of this had universal support among the European elites, let alone the common folk, because people are generally afraid or unsure of change, especially if they have a vested interest in the status quo, and it takes time for new ideas to become well-known, mainstream and fully implemented. Thus, while the proposals of the Enlightenment were debated and discussed, few became a reality. Their most immediate product was a form of despotism where absolute monarchs cultivated the new intellectual culture, presenting themselves as enlightened and enacting some reforms, though ultimately to strengthen or expand royal authority. Three examples are Frederick II of Prussia (1740-1786), Joseph II of Austria (1764-1790) and Joseph I of Portugal (1750-1777) – or rather his chief minister, because the king had a deep interest in recreational affairs.

Two revolutions changed that: the American in 1776 and the French in 1789. Having removed existing powers by force – colonial rule in one case, that of an absolute monarch in the other – the way was open for the ideals of the Enlightenment to be more fully implemented. Hence the US Declaration of Independence expresses the belief in natural rights, common equality and government by the consent of the governed, the US Constitution established a separation of powers, while the Bill of Rights legally consecrated that of Church and State and offered a series of individual rights. In France, the old medieval parliament became the National Assembly, which abolished the country’s feudal system, approved a declaration of rights and duties of citizens and, in 1791, a constitution that limited the authority of the Crown and Church. Two years later, after a failed attempt to flee the country, the king was executed and a republic proclaimed. It was a crucial moment: in the world of the enlightened despots, the monarch was sacrosanct, so for one to be put on trial and beheaded was a shock. It was a radical expression of the notion that the law and will of the governed are above dynastic claims and royal authority, something that could not be tolerated by other monarchs. As a result, neighbouring powers declared war on France, with the ensuing conflict and instability eventually leading to the rise of Napoleon in 1800. While he was an autocrat, the Napoleonic Wars of 1803-1814, during which much of Europe came under French occupation, were nonetheless the vehicle through which the revolutionary ideas of 1789 were disseminated, producing a series of liberal uprisings and regimes within a few years. In essence, the birth of modern European democracy. And the rest, as they say, is History.

What does all of this have to do with recent discussions among polytheists? One word: perspective! See, it all comes down to the starting point, because while the United States were a product of the intellectual culture of the 18th century, many European countries are much older than that and go back to the Middle Ages. This allows its modern citizens to make a comparison between the status quo before and after the late 1700s and honestly conclude that the Enlightenment lived up to its promise of liberty and equality. Not instantly, but slowly, because ideas take time to develop, to go from novelty to mainstream, and generally not without opposition and shortcomings.

Here’s a practical example. The first Portuguese constitution, which was rectified on 23 September 1822, was a short-lived text that remained in force for less than a year, because it was considered too liberal, too revolutionary. It enshrined freedom of press and speech, the inviolability of one’s home, the right to a fair trial, abolished torture, limited royal authority and separated the executive, legislative and judicial powers. Things that seem obvious to us, but which were a novelty at the time, when the prevailing mentality was different from today’s and the ideals of the Enlightenment were only just starting to be turned into law. If you’re not sure about that, hear me out: the 1822 Constitution contained no provision that ensured freedom of religion except for foreigners, who could retain their own faith and practices in private. See what it meant to be too liberal back then? The constitutional charter of 1826 was slightly better and allowed for non-Catholic temples to be built, so long as they had no public visibility as such. In other words, it created a sort of closet where you could be whatever you wanted, religiously, but in private and as an individual person in order to “protect” the beliefs and morals of the majority. Gay men will certainly recognize the strategy. Which is why Lisbon’s synagogue, built at the start of the 20th century, was erected on an inner courtyard and looks like a regular building from the outside. Now, based on that, you could point fingers at the Enlightenment and claim that it either produced restrictions to religious liberty or failed to enshrine it. But that makes little sense to someone like me, because the aforementioned synagogue was the first to be built in Portugal since 1496, when Jews were expelled or forcibly converted. Which means the timid religious liberty of the 1820s was actually an improvement and time showed it to be the initial step towards today’s wide freedom of worship.

This comparative exercise takes on a different shape for a US American, since the United States were only created in the late 1700s. It’s harder to look at freedom and equality in the 18th century – which did not include slaves and natives – and claim that it was nonetheless a positive shift from a previous state of things, because there was no country named United States of America before 1776. Instead, there were colonies and native communities who were destroyed afterwards, which produces a negative outcome when comparing the before and after the Enlightenment, since it heralded the start of a genocidal expansion westward. Contrary to the ideals proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence, which as a result can come across as fake. For US Americans, it can even feel like they’re fighting against the Enlightenment, precisely because of what came after. Or because abolition and civil rights had to be hard won after the 18th century, despite the noble principles declared by the country’s founding fathers. So when looking back in time, which is common when you’re trying to make today better than yesterday, US Americans may find a grim view: either they can’t make a comparison with an older version of their country, leading to the impression that the Enlightenment failed and people had to win their rights and liberties no thanks to the lofty goals of 1776; or they look further back, beyond that date, and find native cultures that were destroyed afterwards, producing an association between genocide and the Enlightenment.

The view is much more positive on this side of the pond, since most of western Europe’s nations date back to the Middle Ages and went through a feudal age, despotism and centuries of religious wars and intolerance before reaching the 19th century. So when comparing the before and after the late 1700s, we can honestly say that there was an improvement. Because religious liberty, public education, separation of Church and State, the abolition of slavery and the death penalty, healthcare, voting rights, the presumption of innocence – all of this are things that did not exist in our countries before the Enlightenment. They came after it, precisely because they are the product of its ideals. In as much as modern Europeans can look at things like gay marriage, which wasn’t even conceivable for men like Locke or Voltaire, and still see it as a product of the Enlightenment, the latest development of a natural right to life, liberty and happiness.

2. Modernity

This then ties with the notion of modernity, which in western Europe normally has a good connotation. Because when we look back in time, we see a positive progress between what our countries looked like before the 1700s and the social, political and civil rights and liberties we acquired between then and now. Not in a linear fashion, but overall. Even decolonization can be seen by a European as a product of modernity and not something that happened in spite of. Because what is the end of colonial rule if not a more recent upholding of a natural right to liberty and of the governed to decide who governs? Surprising as it may seem to some US Americans, because their country’s History might suggest otherwise, Europeans can see the right to self-determination as a modern development of the ideals of the Enlightenment. That they were produced in Europe and later came back to bite it is no contradiction or at least no more than the ideas of a British philosopher being used in 1776 against British colonial rule. Yes, I’m talking about John Locke.

Is modernity unproblematic? Certainly not! It brought its own share of horrors and challenges, from the human catastrophe that were both world wars to the environmental issues of our time. And yet, here too lies a difference in experience and perspective, for whereas on this side of the pond I find an optimism about modernity’s ability to solve those problems, among US polytheists I am often confronted with the opposite view in the form of an anti-modern attitude.

This is not entirely surprising. For one, because the starting point is different: as said, whereas Europe’s History has provided its western citizens with a positive view of modernity and progress, the same cannot be necessarily said of US Americans. Which is why some will say “no” if asked whether today’s problems can be solved by modernity, since some (or many?) US polytheists feel like they’ve got little or nothing from it so far. And this then couples with current politics, where there’s a gap between the two sides of the Atlantic with regard to environmental policies and the role of religion in public life. While in Europe, fighting climate change is mainstream and an increasingly important policy vector, in the US, one of the two main parties commonly denies that climate change is real; while there’s a growing investment on renewable energies on this side of the pond, things may look somewhat grimmer on the other side. And there are other matters where a similar difference can perhaps be found: circular economy, food waste and quality, environmental law, public transportation, etc. Furthermore, whereas Christian fundamentalism plays little role in western European politics and is normally confined to fringe groups, it is a considerable part of the electoral base of one of the two main American political parties. And as a result, the pressure of the religious right on lawmakers is much smaller on this side of the Atlantic. The Catholic Church is normally the main opposition to modernizing policies and historically it has been pushed back progressively (noticed the words I used in this sentence?). This is different in eastern Europe, which missed much of the secularization of the 19th and 20th centuries and suffered under the official atheism of the Soviet period, resulting in a religious backlash starting in the 1990s and a much stronger influence of the Catholic and Orthodox churches than elsewhere in the continent.

So when you take all of this together, there is a trend that may be summed up as follows: whereas European polytheists can feel that they’re polytheists thanks to modernity, because they enjoy a religious freedom that did not exist in their countries before the 1700s, some of their US coreligionists might feel that they’re polytheists in spite of modernity, because the Enlightenment did not bring the secularization that it did in Europe and they have no way of making a positive comparison with what existed before 1776. And while Europeans may look at the comforts and advantages of the modern age and feel that its downsides may be solved through better, more efficient and cleaner progress, a darker view of modernity may be found among US polytheists, given their country’s History and the current political climate.

The Inquisition at work in 18th century Lisbon. You might want to reconsider if you think progress brought us nothing.

3. Christianity

There’s something I’ve been saying throughout this post which may seem problematic to some: that the religious freedom enjoyed by western Europeans today has never existed in their countries. Which is true, though I have no doubt that there are those who will quickly point out that pre-Christian Europe was equally tolerant or even more so. But that, I’m afraid, is false and for two reasons.

The first is that religious liberty in the ancient world was limited by political authority, in that what you believed in and above all practiced was essential to determine your loyalty and hence legal status. If you happened to live in the Roman empire and didn’t want to worship the emperor or at least pray for him, chances are that you’d find yourself facing the sharp end of a sword. And if you found certain traditional practices reproachable and refused to take part in them, there was a strong possibility that you’d be dragged out of your home, expelled or even killed, especially in the case of something like a plague, draught or military defeat, which you’d be blamed for. This was true even in a polytheistic society, where you had the freedom to worship whomever or whatever you wanted, so long as you stayed within certain limits. Also, there could be restrictions if your practices were deemed immoral or linked to an enemy country. Check under Magna Mater and Egyptian cults in ancient Rome.

Today’s religious freedom, while not perfect, is nonetheless much less restricted and hence better then what was the case in ancient Europe. You’re free to worship whomever or whatever you want without being legally labelled as a traitor or sentenced to death by virtue of your choice of religion. Conservative or nationalistic groups may no doubt disagree, but there’s a difference between a person’s views and the law of the land. Otherwise, we’d have the death penalty simply because some are in favour of it. The same is true for accusations of bringing down natural disasters or being legally discriminated against because you happen to follow a religion that’s predominant in an enemy country. Or at least that’s how it normally goes in western Europe, though it may not feel that way in the US, namely in the deep south and Midwest, where the religious right has a stronger influence on lawmakers.

But a more crucial element here is that I’ve been talking about religious freedom in our countries and the fact is that many western European nations did not exist in the pre-Christian period. It’s true that their territories were not uninhabited, but those who lived in them did not see themselves as part of a political entity named Portugal, Spain, France, England, Italy or Netherlands until the Middle Ages or much later. Which is why I find it amusing when fellow polytheists from across the pond tell me about “what the Church did to my country” as if it was already in existence in the centuries BCE. It wasn’t! Portugal only became a kingdom in 1147 and at best its origins can be traced back to c. 868, when the county of Porto or Portucale was founded. And by then, there wasn’t much in the way of pre-Christian religions in the region other than folklore, rural traditions and elements that had been absorbed by Christianity in the preceding centuries. The same can be said of Spain, a name derived from the Latin Hispania – i.e. the Iberian Peninsula – but which became a political entity only in 1469; at best, the notion of Iberia as a unified State can be traced back to the Visigoth kingdom, though it too was Christian. France is trickier, because you can always point to the Franks, but keep in mind that they were only unified under a single realm in the late 5th century under Clovis I and by then many of them were Aryan Christians.

So unlike Iceland, Ireland, Denmark or Norway, my country doesn’t have a well defined pre-Christian identity since it was born after the Christianization of its land, which before the 9th century was inhabited by pre-Celts, Celts, maybe Phoenicians and some Greeks, Romans, Germanic tribes, Arabs and north-Africans, all of which brought their beliefs and customs, but were assimilated and subsumed centuries ago. That’s also why this is a country where different traditions can claim to be native in some way, because the cultures that produced them once called this land “home”. And that includes Christianity, which has been in western Iberian for roughly 1500 years. To call it invading, colonial or genocidal when referring to its impact on Portugal is ridiculous at best.

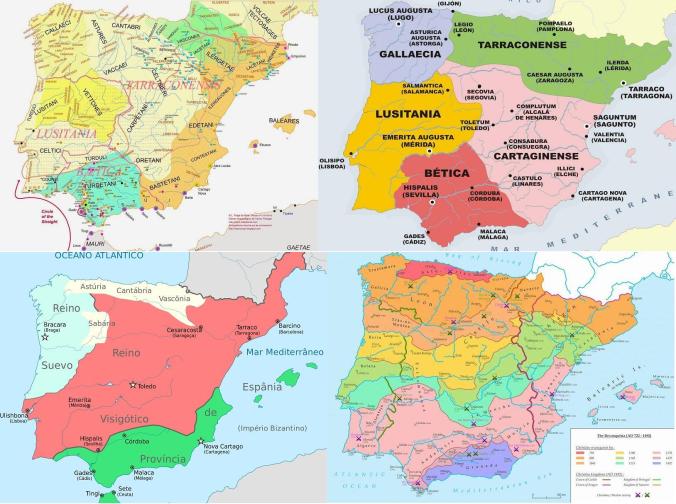

Left to right: Iberian tribes and early Roman provinces (c. 200 BCE – c. 300 CE); later Roman provinces (c. 300 – 410); Germanic Iberia (c. 500); the “reconquista” (c. 750-1492) after the Arab conquest of the peninsula in 711-14.

This has multiple consequences. For one, I’m not a Lusitanian, Suebian or Visigoth, because those are identities that vanished over a thousand years ago. People who saw themselves as such are no doubt counted among my distant ancestors, but that doesn’t mean that I inherited their tribal or national identity. This is unlike what happens in the US, but that’s because many Amerindian cultures were only wiped out or forcibly integrated into the United States of America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Simply put, it’s a fresh wound, whereas over here it’s something that happened a millennium or more ago. European tribes were conquered and assimilated by Romans and medieval kingdoms and have long been integrated into current national identities – sometimes in a contradicting fashion. Go to London and near Westminster Pier you’ll find a statue of queen Boudicca; go to the Tower Hill, still in London, and you’ll find a statue of emperor Trajan. Two historical figures from opposing sides – the colonized and the colonizers – both being honoured as part of the historical heritage of a modern nation. Time has healed, integrated and reshaped identities, fusing old enemies into a national whole, and it would make no sense for modern Britons to protest against Roman imperialism, atrocities and occupation of British lands. Not so in the US, where colonization is a much more recent process.

The same logic applies to views on Christianity, for whereas missionaries were active destroying native American religions and cultures as late as the 20th century, that same process took place in western Europe over a thousand years ago and generally before our modern countries were born. And because of that, because I’m not a member of an anachronistic Lusitanian tribe or Roman city-State, but of an existing nation that was founded after waves of Christianization, I honestly don’t see Christianity as an enemy or a foreign element. It’s been here for 1500 years and it’s a part of my country’s History and culture. Simply put, it’s gone native, like Celtic and Roman polytheisms before it. It doesn’t mean that I should be Catholic just because I’m Portuguese, that the atrocities of the past should be forgotten or that Catholicism should have privileges. But neither does it mean that I should have a belligerent attitude of “us versus them” out of an ill-digested historical memory. Even more so when you consider social life in western Europe.

4. Secularism

One thing I found curious in previous discussions with American polytheists was how quickly the notion of being secular was interpreted as meaning an absence of religious beliefs. Which is probably a good example of how polarized things have become in the US, with an alarming decrease of the middle ground.

When I say European polytheism can be more secular, I’m not referring to the performance of rites without belief or of labels out of mere cultural significance. I’m talking about a secular attitude, not ideology, in that you can be devout and deeply religious, but without being “in your face” about it. This means you can have sincere and strongly held beliefs, but still be able to relate, talk and discuss with other people about a myriad of subjects without bringing your religion into it all the time. You can debate climate change, abortion, the economy, education or civil rights on their own terms and without turning every single one of them into a matter of theological principles or freedom. It doesn’t mean that there’s no room for religion outside the private sphere or that every mundane action doesn’t have a religious equivalent, but there’s a difference between being a part of public life and being the total sum of it, between having an equivalent and being one and the same.

There are historical reasons for this. Europe had multiple wars of religion, both before and after the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s, and that affected European politics and society deeply, because after centuries of bloodshed over which religion was right or better, we created mechanisms that allow us to agree to disagree and still get on with our lives as communities. One of them was the secular State, whose origins can be traced back to John Locke’s Letter concerning toleration, clearing the way for a neutral government that can serve and protect all regardless of religion or lack of it. And a concurring notion is that of having a national identity before a religious one. This wasn’t instantaneous! The fact that the aforementioned Portuguese constitution of 1822 did not recognize freedom of worship and that subsequent texts did little to advance it goes to show how hard it was to disconnect nationality from religion. It took its time and it’s not a done job yet. But by and large, we’ve reached a point where we can have a polytheist, an atheist, a Baptist and a Catholic in the same room discussing a variety of issues without going religious on each other. And even when we do pull out faith-based arguments, we can still get along and work in the same volunteer centre because we’re humans and citizens before we’re of that or this religion. This is very much a modern thing. It would have been unthinkable in the ancient world, where religious identity was an extension of social and political ones. But I’m okay with that difference. If anything, I much prefer what we have today, because it makes things more open, less limited by the aforementioned restrictions to freedom of worship in the ancient world. It doesn’t limit your religious choices through nationality.

The Massacre of Saint Bartholomew’s Day (France, 1572). When having a different religion had extreme political consequences. We’ve been there.

Of course, there are national nuances to European secularism: in France, there’s a much stronger stress on national identity, to the point that an individual’s public life is expected to be almost as neutral as the State; this is not the case in the United Kingdom, which is unsurprising, since it still has a national Church and clerical representation in the upper house of parliament. Over here, things are somewhere in the middle, with a secular State, but a public life that can and does have religious participation. Overall, it’s a climate where people can genuinely get along and discuss things without constantly putting religion on the table or going vitriolic about it all the time.

This may not be the case in at least part of the United States, where faith is a common part of the political debate and that’s despite the First Amendment. In as much as you sometimes get the impression that just about anything you say or do across the pond can be seen as having a religious motivation or consequence. But if you don’t have a secular skin or identity, if you wear your religion all the time as if it’s the sole thing that characterizes you or the sum of your being, then everything you say and do will be religious, from your political views to your fashion options and eating habits, with little or no room for a thematic distinction. Which then results in a dynamic where there’s a good chance that disagreements on just about anything will be religious, too. Maybe we should put that under the category of “recent events where groups use polytheism to forward political agendas” or “having a hard time separating the two”. Just saying.

Onward

Where does this lead us? Hopefully, to a better understanding of national idiosyncrasies and hence the whys of each other’s views, though that doesn’t mean we’ll agree or be on the same side on everything. Don’t ask me to condemn the Enlightenment, reject the notions of modernity or progress or fight Christianity because that’s far from my country’s History, its culture and how I experience the world. And don’t ask me to make other people’s perspective my own either, as that would be as ridiculous as telling a native American to honour Christopher Columbus or an Italian-American not to. You are who you are, a product of past causes, and different people have been shaped differently by History. We have to learn to deal with it instead of freely throwing around accusations of “privilege” or “ingratitude”.

Hopefully, time and a greater awareness will also produce a more diverse polytheism where you don’t have to be militant, overly devout, left wing, non-secular, anti-modern, anti-something-else or protest-oriented in order to be seen as a true, legitimate, consequential or genuine polytheist. You can just be a polytheist regardless of where you stand on a number of issues.

Interesting post! I’ve always found it very ironic that we’ve got mainstream American politicians insisting that America is a “Christian Nation” despite the First Amendment. I’ve even heard them saying the First Amendment only applies to different sects of Christianity, as if the founders didn’t know that other religions existed. That’s hogwash. There are quotes from Thomas Jefferson that specifically mention Jews, Muslims, and Hindus at least. But it just shows how much political power Christianity has over here. I’d much rather live in a “secular” country where religion was a private matter than live somewhere where I have to worry about my boss or my husband’s boss finding out we’re not Christians and then figuring out an excuse to fire us. (*Technically* it’s illegal to fire someone for their religious beliefs over here, but they can always come up with some other “official” reason why they did it.)

I’m much more familiar with the UK than Portugal (It’s the only European nation I’ve had the pleasure to visit so far, I have some friends over there, and my husband lived here as a child for a while when his father worked on an Air Force base there), and they have an official national church, yet they also have Charles Darwin on their currency and big marble statues of him in front of museums. That blew my mind when I saw that. Where I live teaching evolution in public schools is still controversial.

So while I tire of how some other pagans constantly bash Christianity (especially since I’ve met some very nice Christians), I can understand where they are coming from. If we had a more secular society where religious freedom was *really* accepted instead of just given lip service, it would be much better.

The dual issues of native American genocide and African slavery also puts Americans of European descent in an awkward position. Like you said, it’s still a fresh wound. People try to justify it because Europeans brought Christianity to the natives and the slaves and saved their souls, so that makes the atrocities committed against them OK. If you’re a person that has rejected Christianity though, like American polytheists, then it starts to look less like progress and more like the Nazi Holocaust. But unlike the Germans who outlawed the swastika, we still have people proudly waving Confederate flags and saying it’s part of our “heritage” that we should be proud of. My mom was actually born in Germany, so does that mean I should be proud of the Nazis and wave swastikas around? Of course not! But now I live in a place where people put Confederate flag stickers on their pickup trucks. It’s nuts. But freedom of speech is also part of the First Amendment. We would never be able to outlaw the Confederate flag here. I just wish that there was more of a sense that it was in poor taste to display it instead of, “Yeah! Good for you! Southern pride!”

I totally get what you’re saying! And in the end, the place where we grew up and live in ends up driving us in a given direction. There’s no action without a reaction and I see why US polytheists may be constantly acting out of a reaction to the religious right.

It is saddening in many ways that the state of discourse in our community of late has reached the point where entries by you and Theanos must focus on discussing the underpinning of topics like this, but you do it beautifully. Your views and explanations are as always a pleasure to read.

Sad, but true. And thank you!

Reblogged this on norsestormr – musings of a heathen and commented:

Without a doubt this is one of the most succinct pieces I have read in a long time that covers a hotly debated topic in the US presently. Not being a resident there, this article resounds with my thinking about the current debate, in ways I hadn’t even realised. I thank you for such a great piece and only hope there are many who will read this, ponder it and benefit from it.

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed it!

Pingback: Location, location, location! « A Polytheist's Ramblings

Aqui no Brasil as coisas se assemelham as dos Estados Unidos. Atualmente temos dois polos extremos, os evangélicos da direita querendo envolver suas religiões na política, quase que dizendo que o Brasil é uma nação cristã (ignorando completamente o Artigo 5º da nossa Constituição), já os da esquerda, esses ficam insinuando como se todo mundo tivesse que fazer protesto e ser militante senão você automaticamente é um hipócrita. É como se as duas forças não deixassem as pessoas serem diferentes, ou você é um ou outro.

Não tenho como falar muito dos outros pagãos daqui pois ainda não tive muitas oportunidades de falar com eles, mas o pouco que conheço eles parecem ser um pouco menos políticos que os americanos (Apesar de que não muito).

Adorei o texto e consegui entender o assunto muito melhor, pois não posso negar que a minha experiência é muito próxima a americana, além do mais vivo na América do Sul. A sua perspectiva como um europeu me deu um novo ponto de vista que talvez que não chegasse nele sozinha.

Obrigado por este texto maravilhoso!

De nada! Compreender várias perspectivas é sempre muito importante.